Mogadishu, 6 December 2025 – Abdi Wali Hassan Hashi is a well-known face on Finnish television.

Over a 25-year career, he has reported across the north European nation, as well as another 48 countries, for a range of Finnish broadcasters, and has won multiple awards for his work.

Over recent years, the 53-year-old, also widely known by the nickname “Wali-Hashi,” has become a well-known face across another country – a place he fled from in the hope of a brighter future more than once.

Beginnings

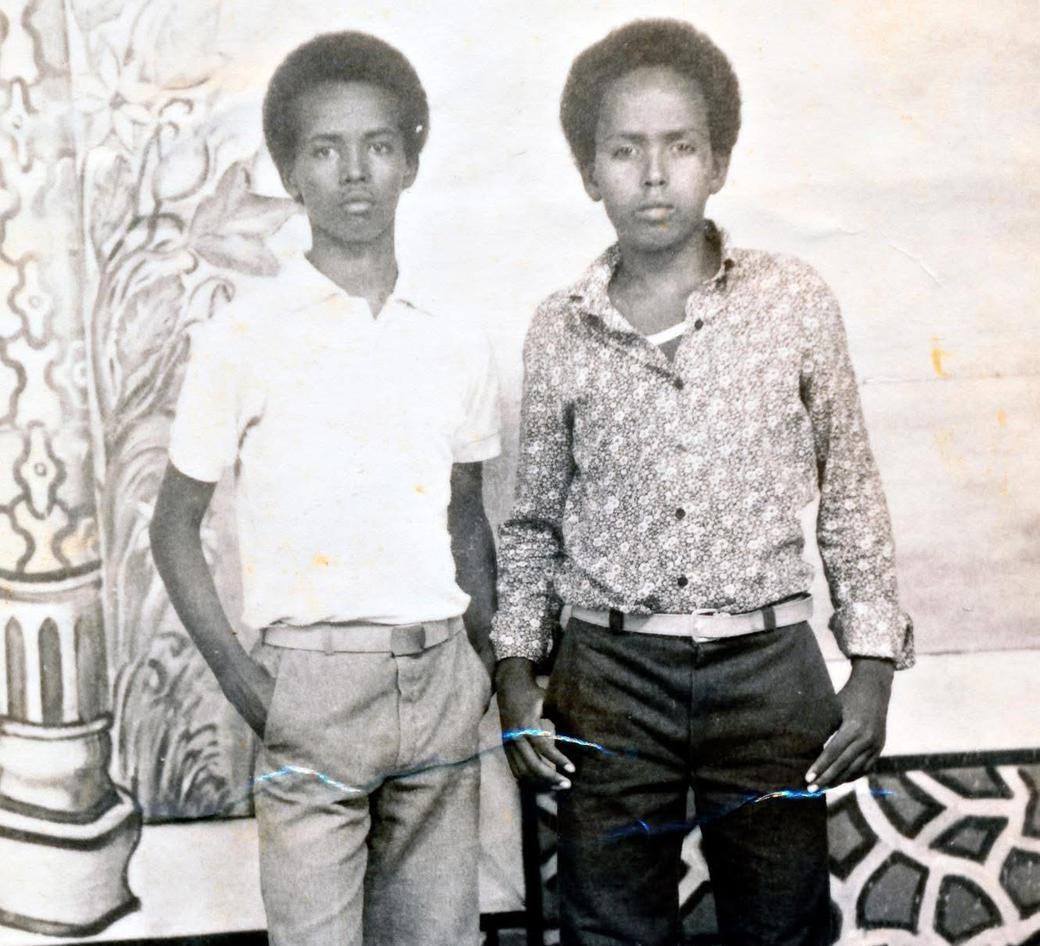

Mr. Hashi was born in 1972 in Mirig, a small village north of Dhusamareb, a city that is now the capital of Somalia’s Federal Member State of Galmudug. But, in the early 1970s, Dhusamareb was a sleepy, dusty town of little national significance.

His early years were marked by hardship. His parents could barely afford to feed him or his three siblings, let alone send them to school. The experiences were hard although now, with the benefit of hindsight, Mr. Washi sees how they helped forge his determination to make something of his life.

At the age of nine, he left his village for Dhusamareb. His mother was not happy about her son’s decision to leave, but she knew it was the right thing if it meant a better life than the one he had ahead of him in the village.

"My mother was not happy about me leaving,” Mr. Hashi recalls. “But there was no reason for her to stop me. I told her I wanted to work, to change our lives, or at least put food on the table. She accepted it, though she doubted someone so young could really help. Still, she hoped I might find something better.”

In the city, Mr. Hashi became a shoeshine boy.

“With no home to return to, the streets became my shelter. The little money I earned, I sent to my mother through travellers returning to the village,” he says. “I remember walking into restaurants to search for leftovers, just to keep hunger away. At the time, education was a luxury I could not even dream of.”

One day, in 1982, when he was 11 years old, he decided he had had enough – he saw no future for himself in Dhusamareb, but the bright lights of the country’s capital appealed.

At the time, Mogadishu was peaceful and offered more job opportunities. And not having enough money to pay for the bus fare was not going to hold him back.

“I begged for lifts from cars heading to the city,” Mr. Hashi says.

Capital start

The hustle and bustle of the capital provided Mr. Hashi with a sense of possibility, and he was determined to make the most of any opportunities that came his way.

“Mogadishu offered better opportunities than Dhusamareb,” he says. “In the city, I washed cars, slept at a relative’s home, and later, with his help, after two years I enrolled in carpentry training at a woodwork shop.”

The capital was widely considered one of Africa’s most beautiful cities, with a thriving cultural and social scene, and the country’s economic centre.

But it started to change. Civil war had yet to descend on the city, but tensions were growing as opposition voices started to be heard against the authoritarian regime of dictator President Siad Barre, both in the capital and across the country. As well, the country’s economy was starting to falter.

None of this was known to the teenage Mr. Hashi – all he could tell was that his existence in the city was getting tougher by the day.

In 1987, at the age of fifteen, Mr. Hashi came to another decision: even Mogadishu could not promise him the future he sought.

He turned to ‘tahriib’ – as Somalis call the often-dangerous journeys using people smugglers to reach foreign shores – for a better life abroad. He smuggled himself on to a cargo ship bound for Saudi Arabia and, soon after arriving there, found a job repairing home appliances in the port city of Jeddah.

“It earned me good money, and I brought my mother from the countryside to live in Mogadishu,” he says.

After two years, however, Mr. Hashi’s undocumented status led to his arrest and deportation back to Somalia.

Yet, he was not discouraged. He had been able to save some money and had had his eyes opened to opportunities.

He used his savings to buy land in Mogadishu. He tried to start a new life, again, but by this time the situation in the capital and across the country had deteriorated further. Somalia was on the brink of civil war as different armed groups vied for dominance.

The outlook worsened.

“It had already been difficult to imagine a future there, the economy was struggling, jobs had disappeared, and people were beginning to lose hope. Many Somalis were looking beyond the borders – towards Europe or the Gulf – in search of a better life. Those who remained lived between uncertainty and perseverance, holding on to the small hope that tomorrow might be different, and I was one of those who decided to leave, believing that somewhere else, life might finally offer a chance to start again.”

Finnish start

In 1990, another opportunity for ‘tahriib’ arose. Mr. Hashi was able to secure a visa for Russia and, from there, some three days later, he eventually made his way to neighbouring Finland, seeking a fresh start.

Mr. Hashi started anew on 25 May 1990, as a 20-year-old refugee with no formal education and no contacts in a new country.

“I was immediately struck by the kindness and dignity with which I was received. For the first time in my life, I saw people being provided with free housing and food, something I had never even imagined,” he recalls. “It was a revelation that changed the way I saw the world.”

Mr. Hashi’s hunger for a better life continued unabated, and he threw himself into his new life, taking advantage of a wide range of classes provided by the Finnish authorities. Within three years, he was fluent in Finnish and English.

However, he kept a close eye on home, where his family remained in Mogadishu, and he worried as the country edged closer to civil war. In 1991, the rising tensions and breakdown in governance finally led to the eruption of all-out conflict.

Mr. Hashi began closely following the coverage on international news channels like CNN, which reported extensively on his home country’s war, famine and humanitarian crisis.

“The news coverage excited me. This shifted my perspective that news can change people’s lives. I was influenced by the news coverage to do the same for my country. To share its stories with the world,” he says.

Journalism career

This newfound interest soon converted into a passion. It led Mr. Hashi to study journalism at Turun Teknillinen Oppilaitos, a government-owned professional school in Turku, in 1996.

As part of his assessment for the journalism course, he had to produce an in-depth news report. For this, he chose to report on Somali refugees who had been seeking safety over the border in the sprawling Dadaab refugee complex in north-eastern Kenya.

At the time, the complex was home to more than 100,000 Somali refugees and asylum seekers, with that number continuing to grow as Somalia’s civil war continued into the 2000s.

“I travelled to the Dadaab camp to report on a Somali girl who had been raped by four men. The story focused on my perspective as a refugee reporting on another refugee,” Mr. Hashi says.

Mr. Hashi’s report was published by a local Finnish newspaper. It fulfilled his graduation requirement, but it did something else: it got him noticed.

The piece also caught the attention of Finnish national media, leading to a documentary about his life titled ‘Cross the Border,’ produced by the Finland’s national public broadcaster Yleisradio Oy – better known by the Finnish abbreviation Yle – and aired in February 2002.

This marked the start of his media career. He began working at a local TV station in Turku, becoming the presenter of one of the city’s most popular programmes and the first Black journalist on Finnish television.

His career path included returning to Somalia in 2009 to produce a documentary – ‘The Pirates’ Coast’ – which earned him the title of Finland’s Best Reporter in 2010. He later joined Yle, for whom he reported on for 15 years and from 48 countries.

Sorted

At this point, Mr. Hashi had felt well-settled and integrated in Finland. His career was flourishing, and he was able to bring his family over as well as marry. On paper, it seemed like he could happily commit his life to his new home.

But a return to Somalia in 2011, to report on the civil war, changed that.

By that point, the conflict in Somalia was felt across society and sectors. Violence was widespread and basic institutions had collapsed. While in Mogadishu, Mr. Hashi heard about the then-Ministry of Information, Post and Telecommunication’s efforts to re-open Somali National Television (SNTV), the country’s main public broadcaster which had closed down due to the conflict.

With a very limited budget, the recently-reestablished broadcaster lacked a range of items considered standard for a television station trying to produce news broadcasts.

“When I visited Somali National TV, I was deeply impressed by the dedication of the journalists and management, who were reporting live on the war against Al-Shabaab day and night, despite lacking the necessary equipment to carry out their work effectively,” Mr. Hashi says. “Witnessing this situation motivated me to do everything I could to help.”

“The state of the national media in terms of equipment was clearly very poor, and I felt a strong sense of personal responsibility. Coming from a modern media environment with advanced resources, I immediately recognized the challenges Somali National TV was facing and knew I had to contribute to addressing them,” he says. “I reached out to the Finnish Foundation for Media and Development (Vikes), asking them to facilitate the shipment. They agreed and, in 2012, I brought not only equipment but also my dedication and expertise to SNTV.”

The experience was a transformative one for Mr. Hashi.

Enthused about the potential and recognizing the scale of the need in his former home country, he approached Vikes about any opportunities and changed to part-time work at Yle so he could dedicate more time to Somalia – his experience and language skills made him a perfect fit to be appointed project coordinator for Vikes’ Somalia programme.

“For me, it was never just about sending equipment. It was about building the foundation of a more powerful press in Somalia, empowering journalists with skills, and giving local voices the strength to be heard,” Mr. Hashi says.

Since then, Vikes, a development cooperation foundation specialized in freedom of expression and the media, has worked extensively in Somalia in support of the development of its media sector. Under Mr. Hashi’s guidance, the Vikes’ programme has trained more than 1,700 Somali journalists across the country.

“The support of the Wali-Hashi team and Vikes has been deeply meaningful to Somalia’s national media,” says Mohamed Kafi Sheikh Abukar, the Director of SNTV. “Their timely and dedicated support has been truly transformative, leaving a lasting impact on the growth and development of Somalia’s state media.”

Forgiveness

Mr. Hashi’s work with Vikes sees him travel around Somalia to provide training to media associations and other civil society groups.

Over recent years, he has combined those travels with another project, this one inspired by his experiences visiting Somalia as a journalist – in particular, an incident that stayed with him from 2009 while filming on Somalia’s eastern coast.

“Those working with me quietly told me to change my clan identity, warning that if I revealed my real background, I could be in danger. Reluctantly, I did. That night, I could not sleep,” Mr. Hashi recalls.

“After decades of civil war, why are Somalis not forgiven each other? That question stayed with me,” he continues. “It became the moment that pushed me to focus on reconciliation and forgiveness.”

In 2017, he founded Cafis – a Somali word meaning ‘forgiveness’ – a grass-roots, non-profit organisation based in Finland, with the aim of helping local reconciliation efforts that bring together communities that have been affected by the decades of war.

Run by eight administrators and supported by 30 volunteers in Somalia, Cafis organises meetings and national events across Somalia’s regions to promote forgiveness.

“We focus on those who have been hurt,” Mr. Hashi explains. “And often, people voluntarily come forward during our events to forgive. Seeing that happen is very powerful.”

“I am hopeful,” he adds, “that initiatives like mine, with proper government support, can create lasting change and reach the whole country.”

UN support

The United Nations Transitional Assistance Mission in Somalia’s (UNTMIS) Political Affairs and Mediation Group (PAMG) supports governance reform and reconciliation efforts across the country.

“Reconciliation is a powerful means by which to help societies heal after brutal conflicts. It can encompass tribunals, truth commissions, reparations programmes and other reconciliation instruments – but it can also include smaller-scale, grassroots efforts like that of Mr. Hashi,” says Vikram Parekh, the PAMG Chief.

“The main aim is to help bring communities together, and contribute to rebuilding Somalia,” he adds. “We hope it continues and can serve as an inspiration to others.”

In May 2024, Somalia launched its National Reconciliation Framework, a tool meant to guide work at the federal, state and district levels, with an emphasis on collaboration across different sectors as well as involvement from elders, religious leaders, women’s groups, and youth groups. Its different pillars include a mental health pillar and a trauma-healing pillar. Within the trauma-healing pillar, it addresses the effects of the 30-plus years of civil war on Somali communities. Another chapter focuses on current events in Somalia, particularly the liberation efforts, and explores how to reconcile communities that have been under the control of Al-Shabaab for over 15 years, returning them to normalcy.